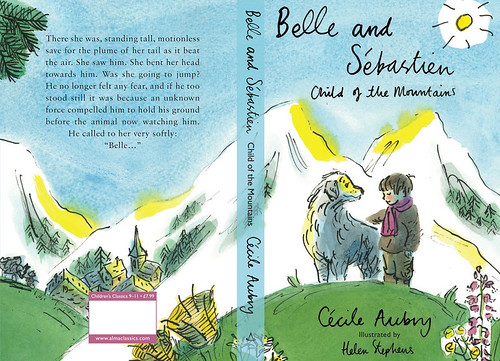

Feeling enthusiastic about Cécile Aubry’s Belle and Sébastien (newly translated by Gregory Norminton), and with the Resident IT Consultant claiming he’d watched it on television as a child (something he rarely admits to), I set about finding out why I only recognised it as a classic book title, but had no recollection of reading the book or being offered it as small screen entertainment.

It made me want to weep. First, because this mid-1960s French children’s novel shows up as a recent film; not even the 1967 television series. Second, because someone has changed the plot so much that they might as well have written a new script about a boy and his dog. And I can find no trace of the book having existed in Swedish translation. I could be wrong, but they are only enthusing about the 2013 film…

This is a lovely book, with illustrations by Helen Stephens done with a real 1960s vibe. Maybe, just maybe, the story is set before the 1964 mentioned in the book, but there are no nazis or fleeing jews and Sébastien’s adopted grandfather does not want to kill the dog Belle. Any nastiness comes from the villagers in this southern Alps French community. That is what the book is about; a boy finding a dog to love, and the ignorant, and scared, villagers wanting to kill the dog they believe is dangerous.

I was thinking that this kind of group unpleasantness would be hard to have in a modern book, and that it clearly shows the passage of time. It works here, though. The period feel is similar to that of I Am David, except this is set almost exclusively in a quiet backwater where the Mayor and the Doctor are the men people listen to.

Sébastien was born in the mountains and his mother died giving birth, so the local gamekeeper brings him up, alongside his own grandchildren. Belle, the dog, was born at the same time, and ends up escaping into the wild when both are six years old. It’s as if they were meant for each other. It’s an easy love to understand. They ‘just’ have to win over the mistrustful villagers who don’t want their children eaten by this ‘beast.’

Really lovely story, which again goes to prove you can have lots of different tales about a boy and his dog.