It’s odd. First, I don’t read that much poetry, or go to poetry events. And then in quick succession I found myself in the Spark theatre for poetry, two events running. Also, out of five poets, three are American. But they explained that poetry is big in the US, in a way it’s not in the UK.

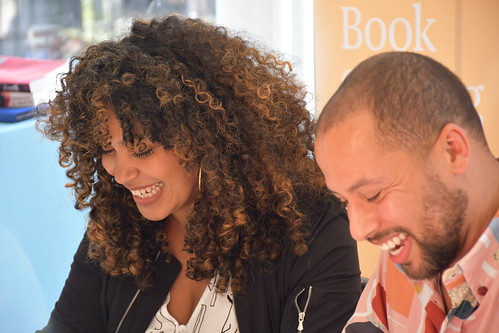

Chaired by Amy McKay, whose flamingo skirt I couldn’t help noticing at the first event (about flamingos), she’d moved on to an equally stunning daisy skirt. And as she said in her introduction of Sarah Crossan, Kwame Alexander and Jason Reynolds; ‘we are really spoiling you this afternoon.’ They really were. She also knew not to waste time on listing all the great stuff the three have done.

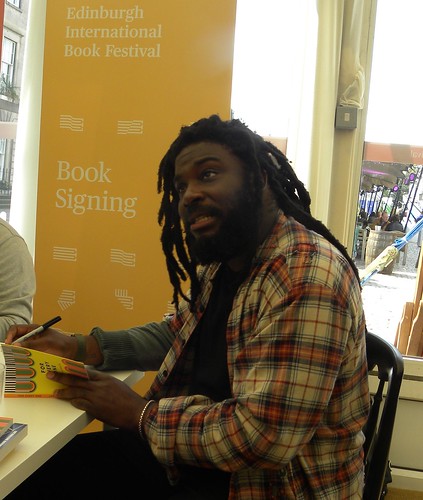

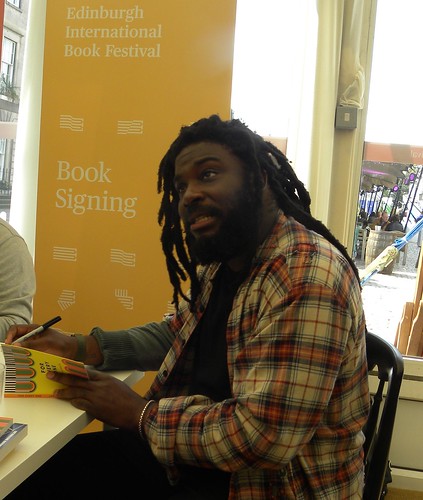

For some reason I’d not realised Kwame wasn’t British, but he’d just moved to London six days earlier, so I was almost right. Brixton has changed in 28 years, apparently. He read his new ‘picture book’ The Undefeated to us, showing the audience the illustrations while he recited his own poems by heart.

This impressed Sarah Crossan, the current Irish Laureate na nÓg, because she can’t remember hers. Maybe it depends on which side of the Atlantic you’re from. She chose to read about Marla and Toffee, the young and the old, and no one listens to either.

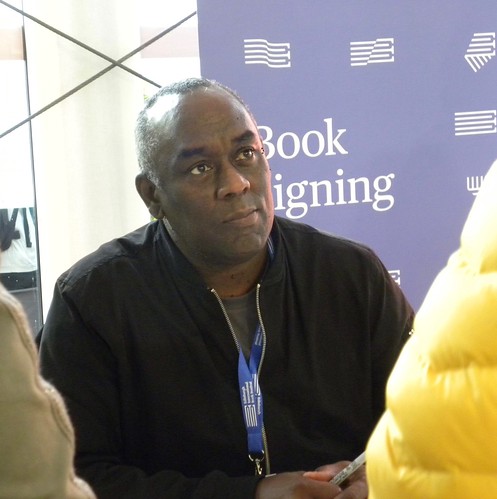

And I finally got to ‘meet’ Jason Reynolds, whom I’d not heard of two years ago when I met someone who enthused about him a great deal. At first he gave a fair impression of a sullen teenager while the other two spoke, but once it was his turn, he sprang to life and you could see why people admire him so much. He mentioned the weather [in the tent], before moving on to gun violence, and talking about how we ‘strap monikers to children so we won’t have to call them children.’

So, anyway, poems are cool in America. Sarah was in luck, writing her first novel while living in the US. According to Kwame poetry is big, but he reckons the publishers don’t know much. He mentioned the impact of Walter Dean Myers, the hero in Love That Dog. Verse novels is quite a new thing, but ‘the kids were already there.’

Sarah is ‘impressed by myself’ and keeps anything she’s written, but edited out, in case she can slot poems in where they are needed. Kwame had many nice poems, but they didn’t go together, so he rewrote.

Jason said ‘it’s my job to keep the rhythm,’ and according to Kwame ‘when it works, the reader forgets it is poetry.’ And he told Sarah that she needs to learn to ‘own her own work.’ She felt that sounded like therapy, and very American.

Kwame went on to mention the American ‘call and response’ to poetry, which is clearly what Elizabeth Acevedo was busy doing a couple of days before, when Dean Atta read from his book. Sarah doesn’t want to manipulate the readers, but Kwame is ‘totally into manipulating’ them… You need to make the world better, and it’s his responsibility to make you feel something. Jason said he’s somewhere between the other two, and manipulation is a dangerous word. ‘I just wanna bear witness.’

Someone in the audience mentioned that with verse novels you don’t have to write the boring bits, which made Kwame quote a secondary school pupil who had described it as ‘the right words in the right order.’

Jason pointed out that writing poetry is like painting with only half a palette, which is harder; ‘really difficult.’ Sarah feels that writing is very democratic, and you only need pen and paper. And it helps if you don’t go to the cinema, don’t have any friends and if you work hard.

Kwame, ‘I steal a lot. Mature writers steal.’

And that was it. The main problem with the event was that it was too short. We could have done with at least another hour. Maybe two. It’s all that poetry, with so few words.