Guest review by the Resident IT Consultant:

‘Looking for something escapist to read, I came across Tonke Dragt’s The Letter for the King (Pushkin Press). The publisher, and the author’s name, led me to suspect that this must be a translation. And I was right.

Tonke Dragt was born in Dutch Indonesia in 1930, spent several years in a Japanese prison camp and came to the Netherlands with her family at the end of WWII. The Letter for the King was her second book, published in 1962. It was very successful in the Netherlands where it sold over a million copies and was chosen, in 2004, as the best Dutch children’s book of the last fifty years. It has been widely translated but only made it into English in 2013.

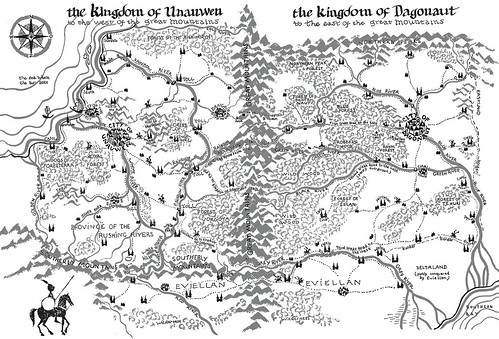

Ever since Swallows and Amazons and Treasure Island I have been captivated by books which contain maps. I even drew my own map for Kidnapped, and when I showed it, aged 12, to my English teacher he lent me his personal copy of The Lord of the Rings. But that’s another story.

The Letter for the King starts with a map of the Kingdoms of Dagonaut and Unauwen. I assume it is the author’s as she is credited for the illustrations, and was an art teacher. I found myself referring the to map quite often as I read the book.

It’s basically an adventure story set in a fantasy medieval world which owes a greater debt to Le Morte d’Arthur than to Tolkien. Tiuri, the sixteen-year-old hero, finds himself suddenly tasked with the challenge of secretly delivering a letter across half a continent. The story follows his development as he deals with the difficulties along the way and tries to decide who he can trust. He learns that first impressions can sometimes be misleading, that help can come from unexpected directions and that hindrance sometimes arises from misunderstanding.

The fantasy is relatively realistic. There are no mythical creatures and there is no magic. Putting geography, and history, aside it feels more like historical fiction than fantasy. Though I think the characters take baths more often than would have been the case in any medieval period!

One strength is the clarity of the language for which, presumably, the translator, Laura Watkinson must take credit. I found it easy and enjoyable to read and it doesn’t feel dated in the way that English books published fifty years ago often do.

I was pleased to see that Pushkin plan to publish its sequel, The Secrets of the Wild Wood, in 2015.’